Pharmaceutical companies amass troves of data. But for most large drugmakers, the executives in charge of those data stores don't make the C-suite.

Only seven of the nearly 30 pharma and biotech companies valued at more than $10 billion rank a chief digital or information officer alongside their heads of science and research on their executive committees.

Six of those individuals, however, were appointed to top management within the last two years — a shift that comes as tech companies like Amazon and Apple inch further into medicine.

Such placements afford greater influence for organization-wide changes, industry watchers say, and signal drugmakers are taking seriously the potential of digital technologies to change how they do business. For some companies, the role existed at lower levels of management, or responsibilities were spread throughout business units.

"Whether it's warranted or not, every company is becoming a data and technology company," said Aarti Shah, chief information officer at Eli Lilly since 2016 and a member of the pharma’s executive committee since 2017, in an interview.

Yet for all of pharma's biomedical innovation, drugmakers don't enjoy a similar reputation on the digital front. Healthcare has been slow to adopt even basic tools like electronic record-keeping and, outside of areas like imaging, use of more advanced technologies like artificial intelligence remains more flash than substance.

The newly appointed chief digital officers will be in charge of changing that state of affairs. As direct reports to the CEO, they are in a better position to push forward projects and secure resources to do so, said Shah.

"The pharma industry is behind compared to other industries in terms of digital disruption," said Bertrand Bodson, chief digital officer at Swiss pharma Novartis since mid 2017, when he joined from U.K. retailer Sainsbury's Argos.

"But, gosh, the impact could be bigger than in most industries."

CDOs moving up

It may be the digital age, but that hasn't meant a CDO in every boardroom.

About a fifth of the top 2,500 public companies globally have an executive in the role, according to results from a 2019 survey by PwC.

CDOs are most common in industries like insurance, banking, communications and retail. As a broad group, pharma and healthcare ranked roughly middle of the pack by CDO representation, PwC found.

Until recently, though, CDOs weren't on many drugmaker executive committees. That's now changing, as the recent spate of executive committee appointments in pharma have put CDOs or their equivalent in top positions at half a dozen of the industry's biggest names.

Since summer 2017, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Pfizer, and Merck & Co. each tapped executives formerly at retailers like Walmart and Nike to run their digital operations. Eli Lilly and Sanofi, meanwhile, promoted from within, naming company veterans to the higher-profile posts.

New chief digital, information officers in pharma C-suites

Karenann Terrell, GlaxoSmithKline

Appointed to executive committee July 2017

Previously CIO at Walmart

Bertrand Bodson, Novartis

Appointed to executive committee August 2017

Previously chief digital and marketing officer at Sainsbury's Argos

Aarti Shah, Eli Lilly

Appointed to executive committee September 2017

Previously non-executive CIO at Lilly

Lidia Fonseca, Pfizer

Appointed to executive committee October 2018

Previously CIO at Quest

Jim Scholefield, Merck & Co.

Appointed to executive committee October 2018

Previously CIO at Nike

Ameet Nathwani, Sanofi

Appointed to executive committee as CDO February 2019

Previously (and currently) chief medical officer at Sanofi

For all six pharmas, the appointments are the first time chief digital or information officers have sat on the companies' executive committees. Bristol-Myers Squibb has had a chief information officer on its senior leadership team since 2016.

(Celgene lists Aijaz Tobaccowalla, its chief information and digital officer, among its senior leadership on its website, but does not name him as an executive officer in its latest proxy statement. He joined in August 2018.)

"It's not surprising that they're allocating specific resources to people in these seats," said Vamil Divan, an analyst at Credit Suisse who covers large pharmas, in an interview.

"They're all talking about the importance of big data, and they're all to some extent behind in using data in their drug development and commercial efforts."

Gold mines of data

Over the past two decades, Novartis estimates it has collected 2 million patient-years worth of clinical trial data. Its labs, meanwhile, house 1.5 million chemical compounds.

It’s a similar story elsewhere in pharma, where researchers toil in laboratories to solve the chemical structures of molecules; clinical studies track results from tens of thousands of patients each year; sales teams meet and log interactions with physicians across the globe.

"We sit on gold mines of data," said Shah, who rose through Lilly's ranks since joining as a statistician in 1994.

Putting that data to better use has become a top priority for pharma, one made more pressing by faltering R&D productivity and rising clinical trial costs.

"Over time trials get more complex, the requirements from regulators get more complex and, because the science gets more complex, we actually measure more things," explained Novartis CEO Vas Narasimhan earlier this year on a podcast recorded by Andreessen Horowitz, a venture capital firm.

"What our industry has really not been great at is deploying technology to make this more efficient," he said, noting estimates that suggest better use of data could cut as much as 20% of a study's cost.

A good deal of that expense is rooted in operational issues: enrolling patients into studies, ensuring protocols are followed and data is properly collected.

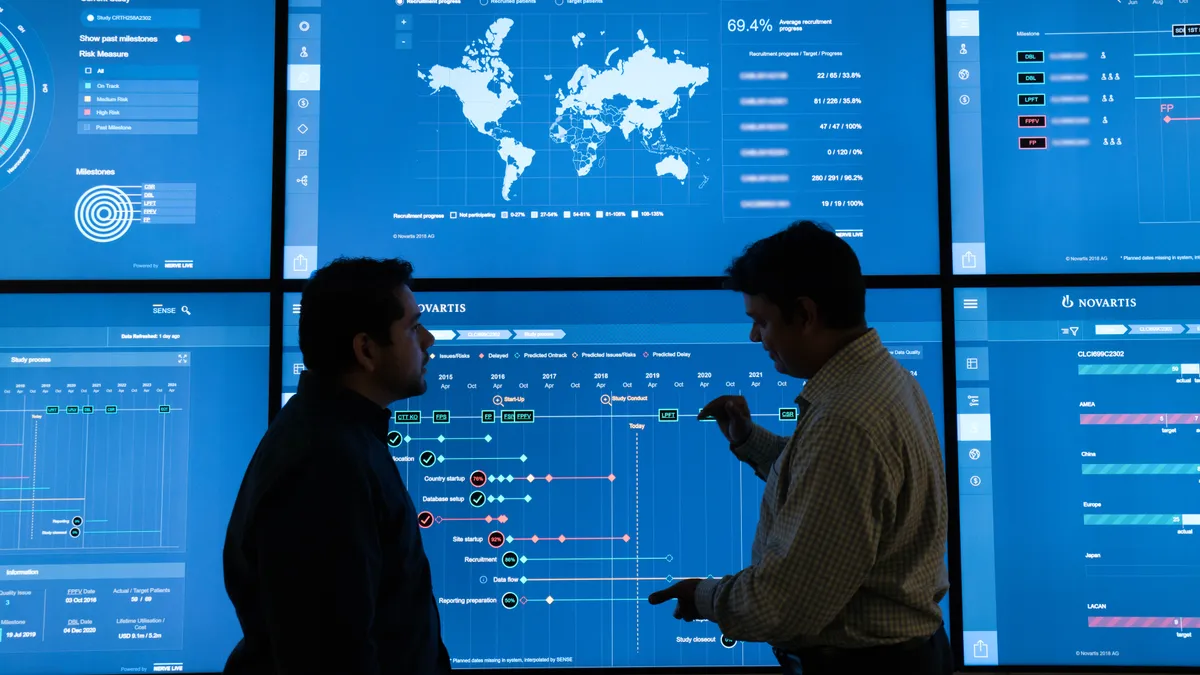

Under Narasimhan, the pharma has launched 12 digital projects across its business, including one designed to use machine learning to predict the performance of the roughly 500 trials the company has underway. (Machine learning, broadly speaking, is an AI technique in which computer models progressively learn from experience.)

For inspiration, Novartis sent staff to observe the electricity supplier Swissgrid as well as aircraft control towers, incorporating lessons on how to better manage clinical trial operations in real time.

Behind the scenes at our new ‘control tower’ to track, analyse and predict the status of all our clinical studies. 500+ active trials, 70+ countries, 80 000+ patients - transformative for how we develop medicines. pic.twitter.com/8lP0zZpQAl

— Vas Narasimhan (@VasNarasimhan) December 11, 2018

Lilly's Shah, meanwhile, points to the two years the Indianapolis company claims it has recently cut from the average time one of its drug candidates spends between first human dosing and commercial launch.

As is the case elsewhere in healthcare, though, drugmakers face an enormous challenge in translating all information they generate into something usable.

"For each disease area, units run their own trials in their own ways," said Novartis' Bodson, in an interview. "We spent quite a lot of energy harmonizing all those data sets."

It's a problem that erodes the immediate promise of AI in drug discovery, too. While better data management and predictive tools are helping drugmakers now with improving operational efficiency, the true test is whether gains can be made in how companies discover and create new drugs.

Conceptually, AI-based methods like machine learning could help comb through, say, a genomic database to find a new disease target. Or the more powerful computer models now available could better correlate the structure of a molecule to its potency as a potential drug.

Practically, however, the data at drugmakers' disposal is messy and complicated by human biology — a constraint that tempers hopes of unearthing new drugs entirely from the information washing through pharma labs.

"One of the big limiting factors in the application of machine learning to the biopharmaceutical space has been the lack of data sets that actually fit the purpose," said Daphne Koller, CEO of data discovery startup Insitro and an expert in AI. "You can glean some stuff out of it, but it's always a struggle and it never gets you as far as you need."

That hasn't stopped companies from trying. Insitro, for example, just signed a collaboration with Gilead to build disease models for the liver disease NASH, aiming to use that information to discover better drug targets. AstraZeneca is doing something similar with BenevolentAI as is Celgene with Exscientia, to name two recent partnerships.

Recent pharma partnerships exploring AI in drug development

| Partnership | Announced | Focus |

|---|---|---|

| Lundbeck with Numerate | January 2019 | Drug discovery in neuroscience |

| Celgene with Exscientia | March 2019 | Drug discovery in oncology and autoimmunity |

| Bristol-Myers Squibb with Concerto HealthAI | March 2019 | RWE and clinical trials in oncology |

| Pfizer with Concerto HealthAI | April 2019 | RWE and clinical trials in oncology |

| AstraZeneca with BenevolentAI | April 2019 | Drug discovery in kidney disease, pulmonary fibrosis |

SOURCE: Company announcements

Like the advent of computer-aided drug design in the 1980s and 90s, though, progress is likely to be slower than press releases might now suggest. Indeed, according to a recent report from STAT, IBM is halting sales of its buzzy AI-powered Watson software for drug discovery uses.

"I would expect the benefits, the real sit-up-in-your-chair benefits, to be a little while away," said Derek Lowe, a drug discovery researcher and author of the industry blog In the Pipeline, in an interview.

"Buf if you wait until people are starting to produce those to go back and get your data in shape, you're probably going to be sorry."

Culture shock

Leading the efforts to do just that will be CDOs. But empowered leadership doesn’t always yield improvement, as the track records of many corporate restructurings can testify.

"If you're a big company, change is hard because it’s cultural," said Alexis Borisy, a partner at Third Rock Ventures who has helped launch biotechs like Insitro, Celsius Therapeutics and Relay Therapeutics.

"It's hard when you’ve got someone at the top who says we need to have AI and reimagine everything we do," he added. "It's not blanket like that."

Koller agrees, noting that data scientists and machine learning researchers aren't always at the table when it comes to designing experiments or making decisions on what to pursue for large pharma companies.

Notably, several of pharma's newest CDOs don’t come from a drug discovery or clinical science background, joining instead from roles at consumer companies.

"If you're thinking about a pharma company as an organization that discovers drugs, the phenotype that you need is very different than the chief digital officers that companies have been appointing," said Insitro's Koller.

R&D leaders who have deep backgrounds in artificial intelligence aren't easy to find, of course — a challenge that extends beyond the boardroom, too.

"We really need a whole new generation of people that straddle the world of machine learning as well as life sciences," said Borisy.