Before Unqork Founder and CEO Gary Hoberman plunged into the tech startup world, he drove innovation from inside the finance industry for more than two decades, developing platform solutions and climbing the IT leadership ladder at Bankers Trust, Salomon Smith Barney and Citigroup.

By the time the founder had risen to EVP and co-CIO at MetLife in 2014, he’d clocked countless hours grappling with technical debt, an occupational hazard for IT execs.

Hoberman declared his own kind of war on legacy code.

“The problem was simple,” Hoberman said. “I spent 80% of my time keeping the lights on and dealing with technical debt vulnerabilities.”

Hoberman focused his remaining time on improving business processes, building and deploying technologies and, unavoidably, generating line upon line of additional code.

“The second that new code goes live, you’ve introduced technical debt into the environment,” he said. “It was a vicious circle.”

Hoberman had run up against a painful paradox of enterprise IT. The technologies driving business transformation are embedded in applications and infrastructure that require maintenance and integrations. Once deployed, those assets devour a big chunk of IT’s resources.

The executive left the C-suite with one big question in mind: “Why am I waiting for someone else to fix these problems?”

Hoberman’s move to the startup world charts an emerging pattern among CIOs who transform their C-suite insights into startup solutions to problems they were once plagued by.

CIOs at the helm

CIOs are moving closer to the core business as enterprises lean harder on IT to streamline operations, propel growth and drive customer experience. The shift brings C-suite proximity for tech executives.

“I'm starting to see some CIOs become the CEOs of their business or move closer to CEO functions,” Hoberman said, noting a Wells Fargo C-suite reshuffle that moved tech executive Saul Van Beurden into a CEO position overseeing consumer and small business banking last May.

Chief technologists have also become more willing to take the startup leap, according to Greg Larkin, CEO of IT executive leadership network Punks and Pinstripes.

“These are people who come to the realization that they can have a bigger impact and make a bigger dent in the universe if they were to leave corporate and start from scratch,” said Larkin.

Hoberman is among the organization’s roughly 200 members, most of whom took a similar journey from C-suite to startup, Larkin said.

CIOs have a direct connection to enterprise solutions that begin as use cases rather than evolving into practical applications.

“I wouldn’t trust someone who is the former CIO of a major insurance carrier to build a social media platform that's going to go viral,” Larkin said. “But I also wouldn’t trust an MIT dropout to build a workflow automation tool for a derivatives trading desk.”

Startups are inherently risky and there are hurdles to overcome. Hoberman’s initiation was sobering, he recalls. His resume got a foot in the door. But the initial meetings were a bust.

“At first, not a single investor came forward and said, ‘We want to be in this journey,’” Hoberman said.

Hoberman, who at the time was in his mid-40s, said he was deemed too old to be starting a tech company.

“I was also told I wasn't entrepreneurial enough — that if I was able to work at Citigroup, there’s no way I could be CEO of a startup,” he said.

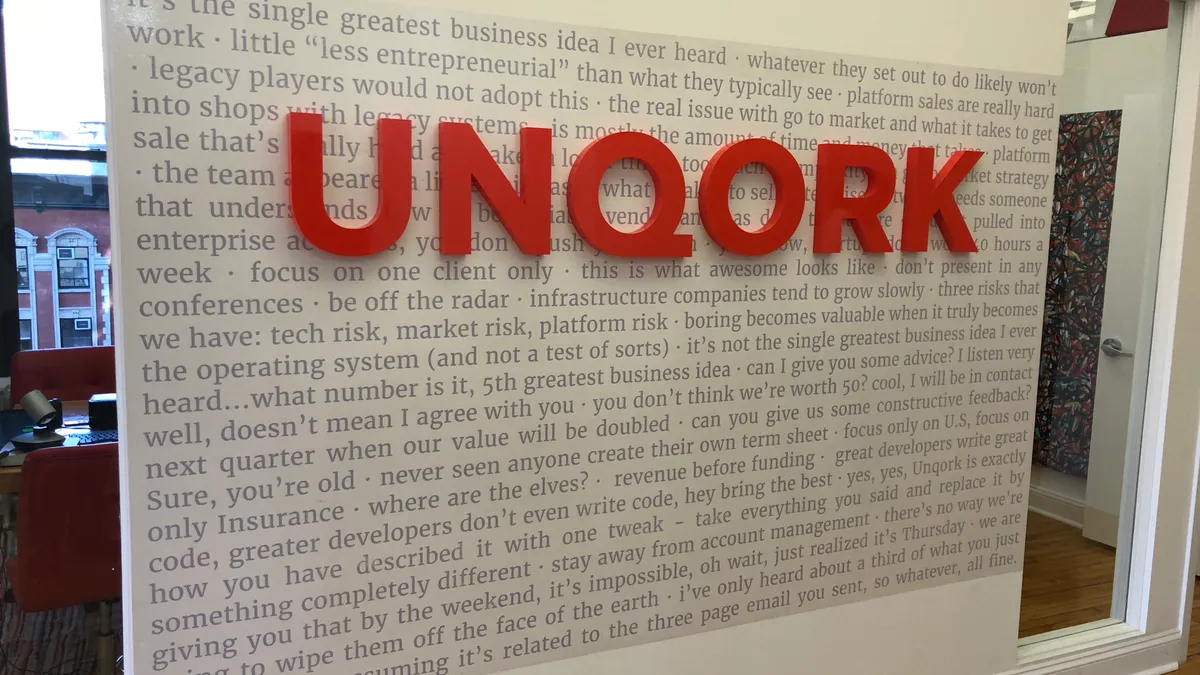

He collected those quotes and pinned them to the wall at Unqork’s offices.

Engineering codeless

Not all CIOs have a strictly engineering background. Business acumen and management skills are a big part of the job.

At Citigroup and MetLife, Hoberman had tens of thousands of technologists and hundreds of millions in budget, he said. But he kept his programming chops sharp and was troubled by the proliferation of low-code/no-code tools and their downstream effects on the tech stack.

“Most no-code tools that exist today generate code,” Hoberman said. “Even with generative AI coding tools, your prompt is going to give you back HTML and JavaScript.”

As far as technical debt is concerned, a faster coding process just increases the volume of what quickly becomes legacy.

“You’re simply generating code faster, which means more to maintain, more security issues, more performance issues and more room for error.”

Hoberman learned that lesson the hard way and is aiming to stem the tide of technical debt with codeless, an as-a-Service solution that delivers pre-programmed enterprise applications for finance, insurance and other verticals.

“Not many people understand the tech stack that supports insurance, regulatory compliance and underwriting,” Larkin said. “The list of people who have that domain expertise and full fluency on the customer, the regulators and the business requirements is a short one.”

The give-and-take between enterprise and tech sector talent is ongoing, Larkin said. As enterprise executives cross over, the movement energizes startups.

“There are two classes of people who have startups,” Nicholas Kolba, founder and CEO of fintech middleware provider Connectifi, told CIO Dive. “There are people who start companies and then they look for a problem to fix. And then there are people who see the same problem over and over and over again, get so annoyed with people not solving the problem and know they can come up with a solution.”

Kolba was SVP and global head of product engineering at Dun & Bradstreet before launching Connectifi in 2022.

Alongside cofounder and CTO Brian Schwinn, Kolba saw financial companies migrating data services and applications to the cloud but still running workloads on desktop workstations that caused interoperability issues.

They didn’t want to wait for someone else to solve the problem.

“We saw there was a frontier of things that would benefit greatly from moving to cloud,” Kolba said. “It took some time to figure out the solution, but I was seeing the problem day in and day out.”